The Euro-to-Dollar Rate: A European Fiscal Response Could Put Long-term Upside on Table

- Written by: James Skinner

- EUR/USD straddles 1.08 after bearish break of 35-year trendline.

- As EU seeks to beef up fiscal response with joint debt issuance.

- ESM utilisation marks first use of mutualised debt issuance in EU.

- 'Corona bonds' still on agenda for EU leaders' meeting Thursday.

© Grecaud Paul, Adobe Stock

- EUR/USD Spot rate: 1.0801, +0.11% on publication

- Indicative bank rates for transfers: 1.0386-1.0462

- Transfer specialist indicative rates: 1.0602-1.6666 >> Find Out More About This Rate

The Euro was steady on Wednesday as the Dollar remained subdued amid a large and coordinated U.S. effort to mitigate the economic threat posed by coronavirus although a European fiscal response was also shaping up mid-week and might soon sow the seeds of a longer-term Euro-to-Dollar rate recovery.

Europe’s single currency straddled the 1.08 handle through much of Wednesday’s trade as market risk appetite and the resulting ebb and flow of demand for the Dollar dictated fluctuations in exchange rates. But the outlook for the Euro is clouded after it snapped a 35-year trendline against the Dollar, and given ongoing strength in the greenback that is at odds with a market consensus which is still looking for a Euro-to-Dollar move up to 1.15 by year-end.

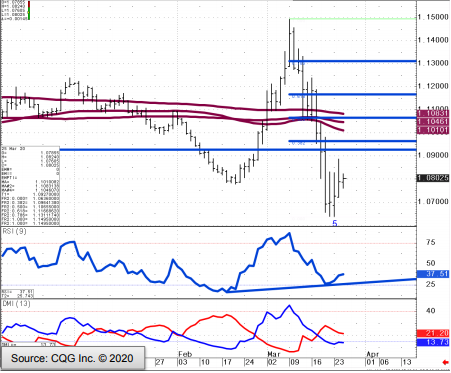

“EUR/USD is upside corrective near term. Rallies should find initial resistance at 1.0926/41, the September and October lows and are likely to be contained by the band of moving averages at 1.1010/83. While capped here our bias will remain negative and attention should then revert to the 1.0636 recent low,” says Karen Jones, head of technical analysis for currencies, commodities and bonds at Commerzbank. “Longer term the market has eroded the 35 year uptrend at 1.0782/74 on a weekly basis. Failure here is considered to be a major breakdown and targets 1.0340, the 2017 low.”

Jones is betting the Euro-to-Dollar rate does not make it in the short-term, past the collection of moving averages marked out by red lines on the below graph.

Above: Commerzbank graph of Euro-to-Dollar rate with technical indicators displayed.

Wednesday’s price action came as investors responded to an estimated $2 trillion U.S. government economic aid package worth around 10% of GDP and intended to help companies and households weather the coronavirus storm that’s disrupting businesses and personal incomes. That came before the German parliament approved a €750bn package of its own and as markets digested the implications of a meeting between Eurozone finance ministers and central bank chiefs in which a European fiscal response was discussed.

So far Brussels' response to the coronavirus crisis has been limited to a €37bn spending package, the relaxation or removal of rules that could inhibit containment of the viral pneumonia and central bank actions, although that is changing quickly and a broader, unprecedented effort could now be agreed upon within days. Discussions and price action took place with much of Europe having gone into an economically damaging ‘lockdown’ in a bid to limit the spread of the disease. Coronavirus is inducing an economic downturn that's already prompted the biggest shake-up of the crisis-fighting toolbox, with the U.S. this week having embraced 'helicopter money' for households.

“The deal reached last night by the Eurogroup means euro-zone countries will now be permitted to use the European Stability Mechanism to finance fiscal spending in response to COVID-19 equal to 2% of each country’s GDP,” says Derek Halpenny, head of research, global markets EMEA and international securities at MUFG. “This we believe is very significant in that it is a clear step toward a joint fiscal response. The ESM is funded as a joint liability and is the first clear step in the direction of a shared fiscal response. While not the same as a new “coronabond” that has been spoken of, it is a step in that direction.”

Above: Euro-to-Dollar rate shown at daily intervals alongside Dollar Index (black line).

Eurozone national leaders are yet to agree on issuance of so-called ‘corona bonds’ on a unified ticket, which would amount to a long-jump from a fiscally fragmented Europe toward a point where monetary union meets fiscal union, but some action was agreed by finance ministers on Tuesday and that might be signed off in Thursday's European Council meeting. The agreement is to allow the tapping of a crisis-fighting fund that provides up to 2% of GDP in mutually underwritten funding to Eurozone members whose companies and households - entire economies - are under siege from the coronavirus.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde, among others, have advocated jointly issued debts billed as ‘corona bonds’ in order to augment the EU response to the viral pneumonia and to help support weaker countries who've little room to borrow and spend. The idea that has since been discussed among member states and in the market, inciting hope that Europe’s fragmented fiscal space might soon be joined up by a crisis-fighting response that would have significant long-term implications for Europe's economies and currencies.

“In the space of 36 hours we’ve done more on global policy changes than we’ve done in 20 years of doing this so everybody who’s on the line saying this is exactly what we did in 2008 and 2009 and it didn’t change the agenda, I think we’ve changed the agenda because helicopter money is radical. Germany opening up the purse is radical. Mutualisation in Europe is mind-blowing if it goes ahead this week“ says Steen Jakobsen, chief investment officer at Saxo Bank. “We are all in the same boat. We have to get this to work and I will trade the market from a positive angle despite the fact that some people who’re much, much smarter than me remain sceptical of this move.”

Above: Euro-to-Dollar rate shown at weekly intervals.

Debt mutualisation could provide the weakest European economies, some of whom are suffering the worst coronavirus outbreaks, with increased capacity to support companies and households through things like wage subsidy schemes that minimise the lasting economic damage done by the virus that’s put all economies under siege to at least some extent. And if such mutualisation is continued beyond the crisis, the more troubled European economies like Italy might one day be able to leave the austere post-crisis period behind and this would be a gamechanger for not only the European Union and its various economies, but for the Euro too.

An economic recovery that reaches the ‘periphery’ of Europe could lift continental growth and inflation, facilitating an eventual normalisation of European Central Bank interest rates that might then encourage a convergence between the Euro and its long-term equilibrium value. More so if such actions are taken at a time when the market is falling out of love with the Dollar. Many analysts estimate that this long-term equilibrium is around 1.20 for the Euro-to-Dollar rate, more than 10% above Wednesday’s 1.08 level, and some even say that it’s way above that - closer to 1.30.

“Germany had already made some concessions with respect to the EU’s budget rules, but it has been resisting joint debt issuance. Instead, it looks like support is building for ESM credit lines,” says Michael Every, a strategist at Rabobank. "The ‘ESM solution’ may not be a sufficient solution to prevent upward pressure on spreads as borrowing requirements skyrocket in the coming months. It is therefore no surprise that, in the call, ECB President Lagarde once again strongly urged governments to consider the joint issuance of “coronabonds.”

Above: Euro-to-Dollar rate shown at monthly intervals.

The combination of a monetary union without a fiscal union has robbed some European countries of all effective means of navigating economic crises, most notably the ones with balance sheets so large that EU rules foist mandatory austerity on national governments. The fragmentation is the result of self-interest and important political considerations from across the bloc, although these have prolonged the recovery of Italy, Greece and others from the financial and debt crises while still lingering today as a threat to the development if-not existence of the Eurozone and European Union.

In a typical crisis interest rates will be cut, encouraging currency devaluation that is often accompanied by increased government spending to soften the blow to an economy. But the current account surpluses of Germany and others have long constrained the Euro’s ability to devalue sufficiently for the likes of Greece and Italy, while the fiscal straitjacket that is the EU’s ‘stability and growth pact’ requires year-after-year reductions in budget deficits (lower government spending) for those heavily indebted countries. Such an approach can sap already limited economic demand and see countries required to run ever faster on a treadmill only to see their GDP do little more than stand still.

“Several Eurozone member states have dismissed the idea, albeit without categorically ruling it out either. The conclusion, then, must be that more market pressure is likely to be a key factor in forcing a decision," Every says.