The Economics of Scottish Independence Look More Difficult: Capital Economics

- Written by: Gary Howes

"Monetary and fiscal policy would then need to tighten to prevent a vicious circle of rising inflation and an ever-weaker currency."

Image © Adobe Images

The economics of Scottish independence are now even more challenging than at the time of the first referendum in 2014, finds new research from independent consultancy Capital Economics.

According to Paul Dales, Chief UK Economist at Capital Economics, challenges have risen as a result of Brexit, the deterioration in Scotland’s fiscal situation and the continued lack of

an easy option for the currency.

The findings were released on the same day Scotland's first minister Nicola Sturgeon said her government would now restart work on a "detailed prospectus" for independence.

Sturgeon told the Scottish Parliament on Tuesday that legislation would at a future date be presented that would set the terms of a second referendum.

Economists will expect any plans put to legislators to offer concrete details as to how a number of difficult financial and economic hurdles can be navigated.

"For Scottish independence to be a success there needs to be clear and credible plans for trade, fiscal policy and the currency," says Dales.

Capital Economics maintain an independent Scotland could be an economic success as are many countries of a similar size in Northern Europe, however the initial adjustment would likely be difficult.

"In its first 5-10 years, an independent Scotland is more likely to fall further behind the rest of the UK than catch it up," says Dales.

Brexit means Scotland would now be required to choose whether to have closer trading relations with the rest of the UK or the EU.

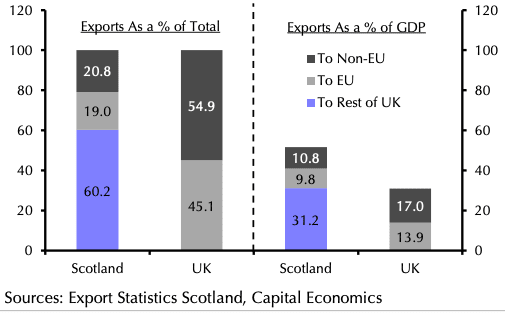

Capital Economics says 60% of Scotland's exports currently go to the UK while 19% go to the EU.

Above: Goods & Services Exports by Destination (2018).

Sturgeon has made it clear on numerous occasions that it is her intention that an independent Scotland would rejoin the EU.

But such a move would inevitably require a hard border for goods between the UK and Scotland, a reality exposed by the Northern Ireland border protocol.

"This risks introducing trade frictions on Scottish exports that are equivalent to 31% of Scottish GDP to reduce frictions on exports equivalent to 10% of Scottish GDP," says Dales.

Capital Economics finds that Scotland's financial position has meanwhile deteriorated since 2014, meaning it will be incumbent on the government of an independent Scotland to put in place credible plans to cut the budget deficit.

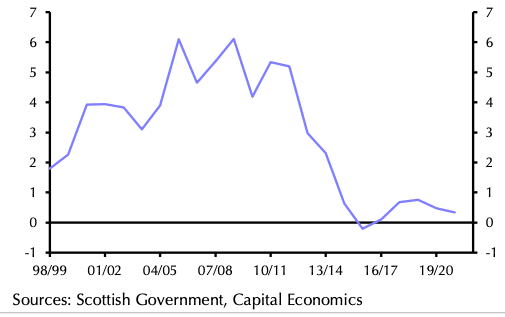

Above: Scottish North Sea Tax Revenues (% of GDP).

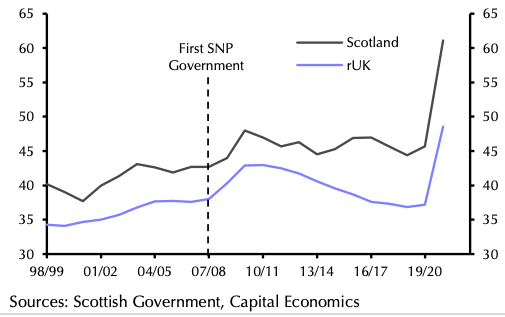

The budget deficit is estimated to be of 9% of GDP with a debt to GDP ratio of 100%.

"Importantly, public debt is likely to be denominated in sterling. Even if we assume that the financial markets judged Scotland’s fiscal plans as credible as the UK’s, a fiscal squeeze of 0.9% of GDP may be needed in each of the first five years (4.5% in total) to stabilise the debt to GDP ratio," says Dales.

He says if Scotland’s borrowing costs were 1.0 ppt higher than the UK's, the fiscal squeeze would need to be 5.5% of GDP.

Above: Government expenditure for Scotland and UK.

Scotland would likely face higher funding costs as investors would demand a premium for holding the debt of a fledgling and untested sovereign entity.

The choice of currency proved to be one of the Yes campaigns major stumbling point in 2014 as they failed to give a concise and clear answer as to what currency an independent Scotland would use.

Capital Economics anticipate that because an independent Scotland would be less productive than the remainder of the UK, Scotland’s real effective exchange rate (REER) may need to weaken by about 5%.

"If Scotland launched its own currency, this would come via a fall in the nominal exchange rate," says Dales.

Sturgeon has said in 2021 that an independent Scotland would continue to use Sterling "for as long as necessary".

Whether this is as part of a UK monetary union or whether it is pegged to the Pound is unclear, but regardless; an internal devaluation is likely required.

"Monetary and fiscal policy would then need to tighten to prevent a vicious circle of rising inflation and an ever-weaker currency. If Scotland kept the pound, pegged its new currency to the pound or adopted the euro, the lower REER would come via an internal devaluation (i.e. a relative fall in domestic prices)," he adds.

Dales warns any devaluation would lead to lower wage growth and higher unemployment as firms cut costs.

EU rules state that new entrants must commit to joining the Euro, therefore should Scotland join the EU an inevitable march to adopting the Euro would be put in place.

"The scale of the policy challenge and the necessary fiscal adjustment makes it more likely than not that an independent Scotland would fall further behind rUK in the immediate aftermath of independence," says Dales.