Boosting Birthrates in China, Thailand, Hong Kong and South Korea is not the Key to Future Economic Success

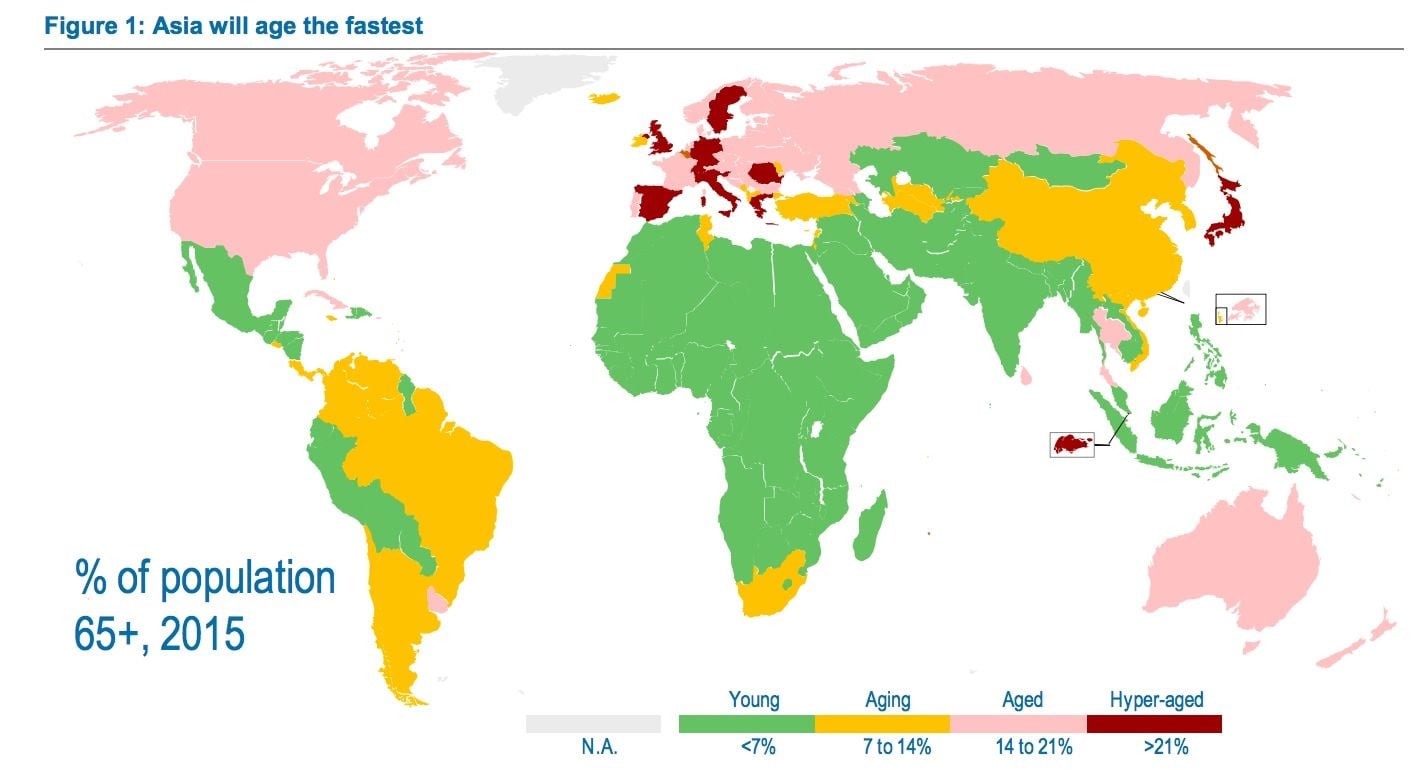

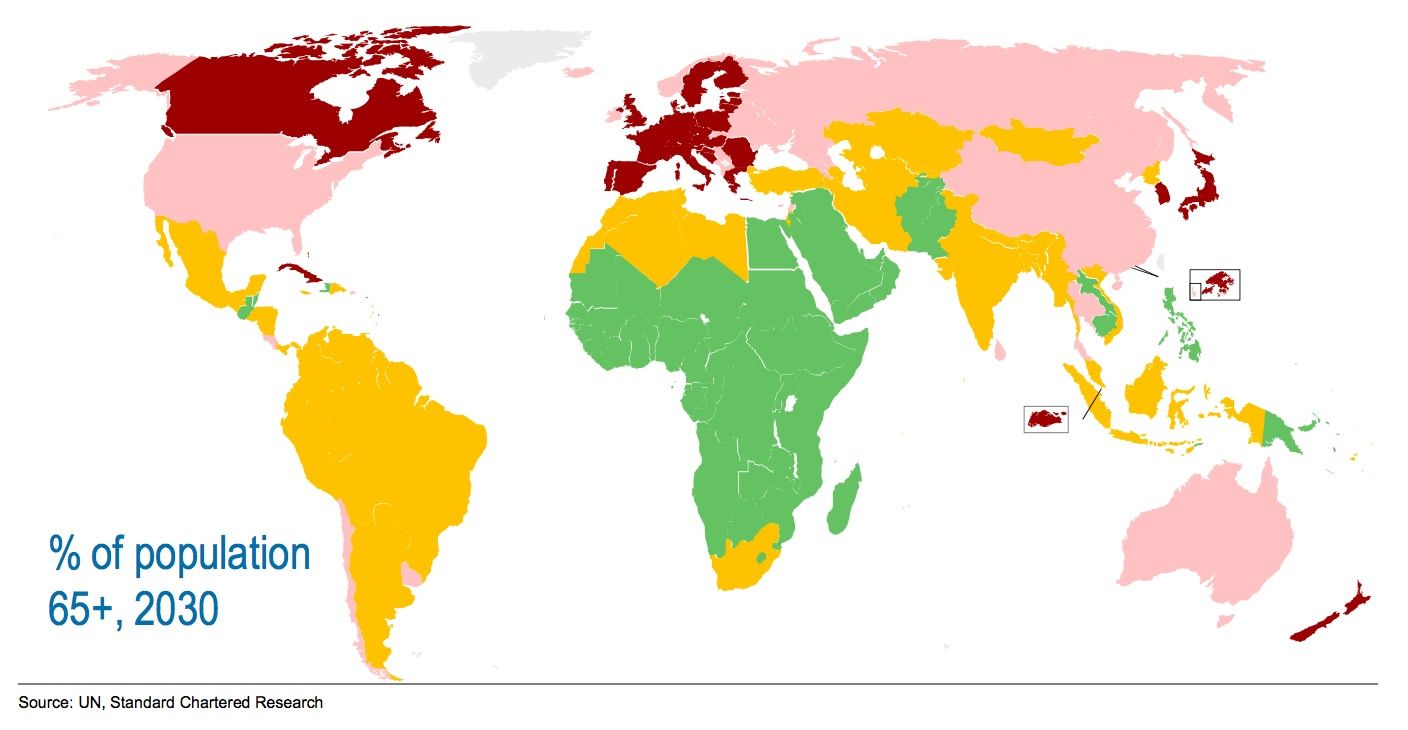

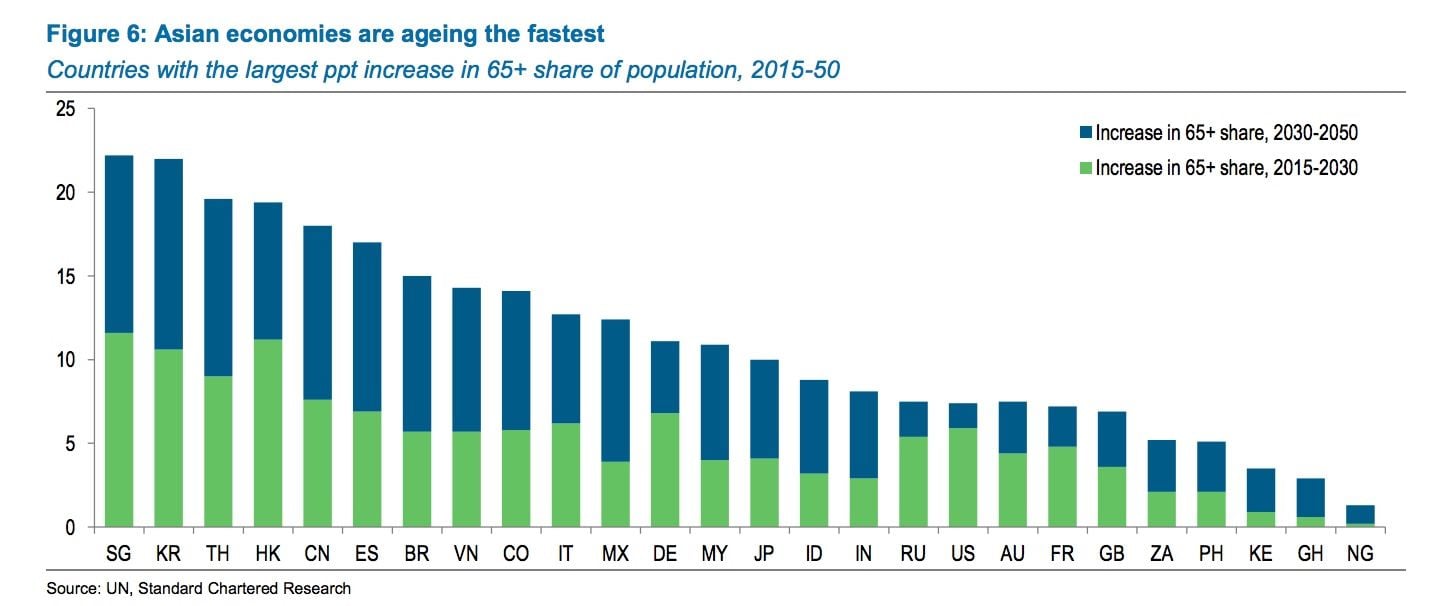

Asian-focussed multinational bank Standard Chartered has suggested policy-makers in China, Hong Kong, Thailand and South Korea pursue policies to boost their populations to counter the negative effects of an ageing population.

The call comes in a recent research note issued by the London-based bank which suggests these nations face challenges associated with low birth rates in the future.

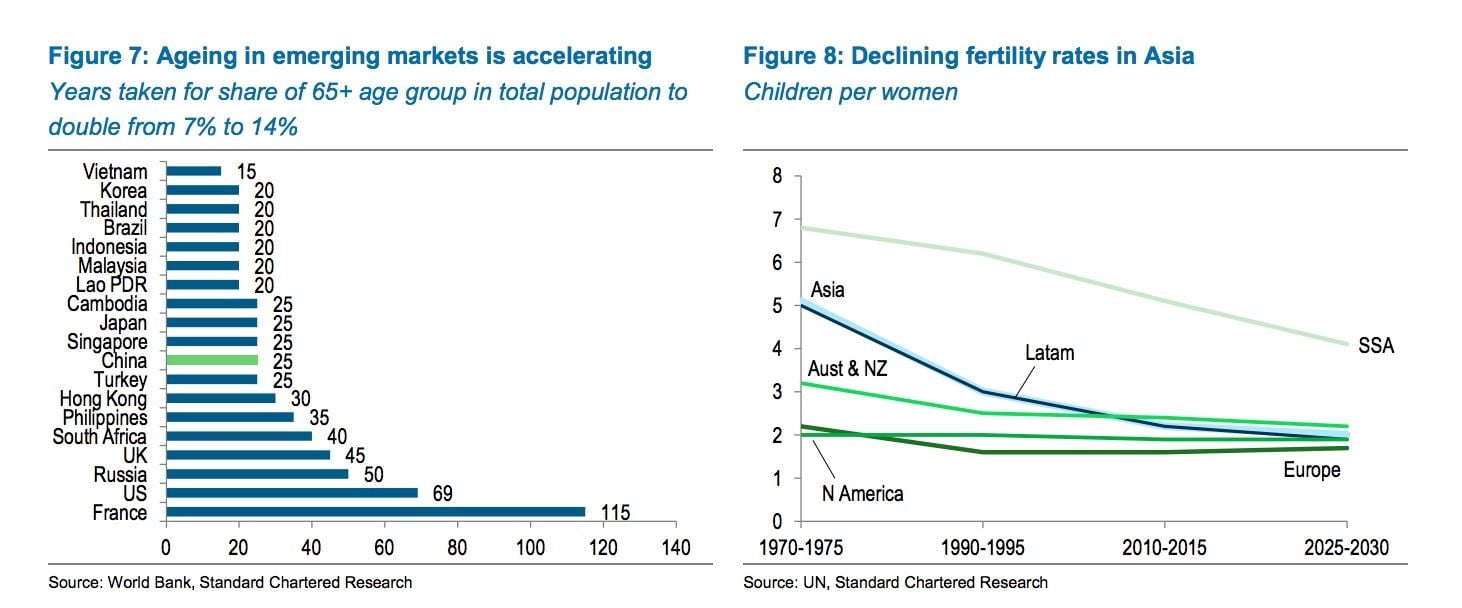

“Ageing is to detract from GDP growth for China, Hong Kong, South Korea and Thailand by 2020 and for Singapore by 2025, according to our analysis. This follows decades of positive contributions. Policy measures, including investing in education and increasing low fertility rates, will be needed to counter the effects of an ageing population,” says Enam Ahmad, Senior Economist, Thematic Research at Standard Chartered.

At the same time Standard Chartered expect India and Indonesia to reap a "demographic dividend" as they enjoy a young working population.

A concern for Standard Chartered is that the acceleration of ageing means some societies will get old before they reach high-income status.

"This could create challenges, including limiting their ability to move up from middle-income status," says Ahmad. "Our projections show that Thailand and China are likely to face this challenge in the next few decades."

Population Ponzi Scheme

What the research fails to address are the risks associated with promoting population growth as a means of boosting economic growth.

The assumption that a rapidly growing population is required to support an ageing older segment of society is akin to a Ponzi scheme.

"The problem with any solution to an ageing society which involves boosting numbers of young people is that young people get old. Whether you do this through immigration or more births, it simply postpones the problem and makes it even more difficult for people in the future to address. It's a patch when we need a repair," says Alistair Currie, Head of Campaigns at Population Matters.

There are a finite amount of resources on the planet after all; and when mega-populations can no longer be sustained the Ponzi scheme is exposed in ensuing societal breakdowns.

"Increasing the birth rate also increases the number of dependent children - resources which could be used to help older people then become tied up in education, child and maternal health and childcare provision such as nursery places," says Currie.

Further, the march of technology and robotics suggests researchers at Standard Chartered are following a paradigm of economic thought that is fast becoming irrelevant.

The idea that economic growth and prosperity is only achieved on the back of a growing population is fast becoming as defunct as those workers technology and robotics will replace.

Standard Chartered’s research however shows that the ageing population is unlikely to dampen Asia’s high household savings significantly in the coming decades.

“The market for seniors’ consumption will also increase rapidly. We estimate that total consumption by the 65+ age group in China will jump to USD 2.8tn by 2030 from USD 0.4tn now,” says Ahmed.

Solutions

Ahmed and his team do expose an interesting point however in arguing that when ageing populations are not adequately planned for they become a headache to Asian governments.

Standard Chartered argues Asia’s pension systems are unsustainable and policy reform options will vary across countries:

“China needs to increase the retirement age, extend pension participation to rural areas, and improve the transparency and governance of state and private pension systems,” says Ahmed.

By creating a more sustainable older population we would arguably not need the spike in fertility that is so often prescribed by economists.

"We can certainly use the skills of older people more to boost productivity but, to give just two other examples, a falling birth rate also means more parents - primarily women - able to join the workforce and the freeing up of money individuals would have spent on children for economically productive uses such as investment pensions," says Currie.

To date Asian governments have recognised the shift in age dynamics with some introducing policies to raise fertility rates to tackle the effects of ageing.

They have so far proven unsuccessful.

Fertility rates for the major economies – including China, Thailand, Japan, Singapore and Korea – remain well below the population replacement rate of 2.1.

Policy should therefore work with changing population dynamics instead of opposing and trying to work against them.

"A falling birth rate also means more parents - primarily women - able to join the workforce and the freeing up of money individuals would have spent on children for economically productive uses such as investment pensions," says Currie.

And here, Standard Charterd's Ahmad agrees:

"Initiatives to raise female labour participation are likely to have the largest immediate impact in offsetting the drag on labour-force and GDP growth from ageing. Child-care provision in places like Japan and Korea has had a positive effect, but their impact has generally been modest, hampered by entrenched social norms."

Measures to upgrade seniors’ skills are prevalent only in advanced Asian economies such as Korea, Japan and Singapore.

This could be something other Asian countries would do well to mimic argues Currie, "a shrinking population in most developed countries will also mean better quality of life - surely the object of economic development".