Eurozone Inflation Miss Highlights Periphery's Plight; Vindicates ECB

- Written by: James Skinner

Image © Adobe Images

Europe's March inflation figures surprised on the downside of expectations Wednesday, revealing in the process that the threat of deflation remains alive and well in parts of the bloc even as prices surge in others, vindicating the nuanced crisis response of the European Central Bank (ECB).

Inflation rose from 0.9% to 1.3% in the Eurozone during March, Eurostat estimated on Wednesday, although the increase came courtesy of rising energy prices that have roots in the international market for oil while the number was itself below the 1.4% anticipated by consensus.

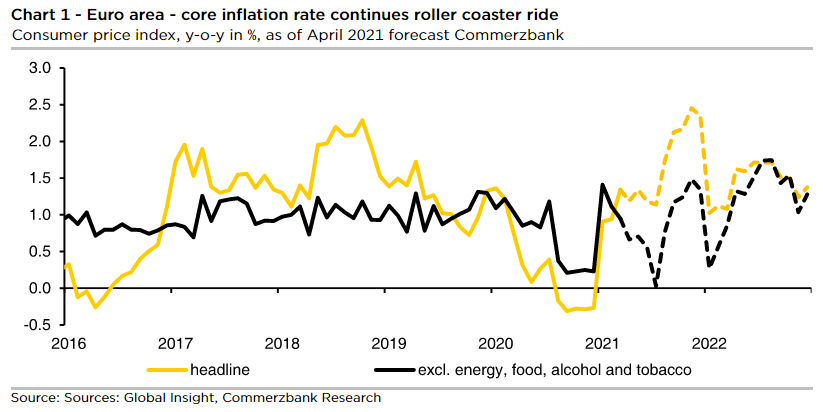

The more important measure of core inflation fell from 1.1% to 0.9% this month when economists had looked for it to remain stable.

This latter measureis taken with greater emphasis by policymakers because it overlooks changes in prices of energy as well as changes in the cost of regulated price items like alcohol and tobacco, which can obscure or interfere with underlying trends in inflation.

"The inflation rate is currently heavily distorted by special factors. Therefore, the underlying inflation should be estimated more on the basis of wage growth, which has slowed down noticeably as a result of the recession," says Christoph Weil, an economist at Commerzbank.

Image © Commerzbank.

Inflation is important for economies, financial markets and central banks, who're charged in most parts of the world with using interest rates and other monetary policies to cultivate steady annual price growth that is generally around 2% for developed economies.

It had been suggested in many parts of the market that extraordinary amounts of emergency cash injected into economies as a result of the coronavirus shutdown would lead to sharp gains in inflation across the developed world at least, potentially prompting some central banks to raise interest rates sooner than they've so far indicated is likely.

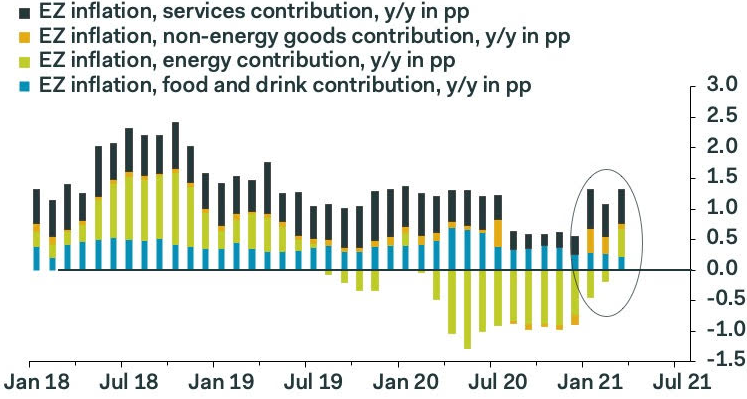

But while inflation rates have surged across the bloc in recent months while in some parts even having risen back to the 2% target level of the European Central Bank, in others the threat of disinflation or even outright deflation has remained alive and well.

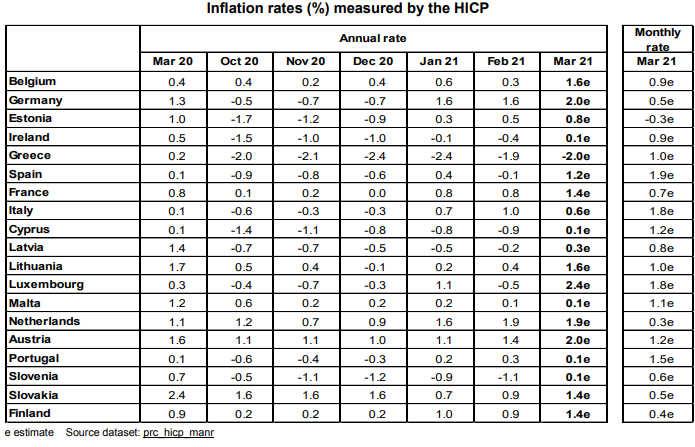

Inflation was knocking on the door of the ECB's target in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands this month, with all reporting annualised rates that were at or even above the "close to but below 2%" level, following a turn of events that may only embolden critics of the ECB's monetary policies who often fear it leading to runaway price growth.

But these risks were not felt or observed so keenly if at all in other parts of the bloc this month, where Greece saw its annualised rate of inflation fall from -1.9% to -2% while elsewhere on the Mediterranean and also in Eastern Europe, annual inflation rates were often close to zero.

Image © Pantheon Macroeconomics.

"We still think an increase in the EZ headline to 2-to-3% is more than doable over the next few months as energy inflation screams higher, though we concede that upside risks have declined compared to our expectations a few months ago. The core will snap back as mean-reversion lifts inflation in non-energy goods, but the trend looks unmoved at about 1%, for now," says Claus Vistesen, chief Eurozone economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

Persistently low levels of core inflation reflect the continuation of what is a long-established problem for ECB policymakers, which is the primary motivator of the quantitative easing programme that has hoovered up around a third of all Eurozone government bonds in the years since January 2015.

The programme is intended to lift inflation by incentivising increased economic activity with lower financing costs. Specifically the bond buying proramme is intended to pass through the ECB's record low interest rates from Frankfurt, to companies and households across the bloc.

However, it's been used in an increasingly nuanced and somewhat controversial way at least since the onset of the pandemic, with policymakers 'overweighting' Mediterranean bonds in their weekly purchases in response to an ongoing need to keep financing conditions favourable for more fragile periphery economies.

Above: Eurostat's country by country breakdown of monthly and annual inflation rates.

This is why in March the ECB pulled forward some purchases - which were already planned to take place - in response to the recent as well as ongoing increase in American government bond yields. That had threatened the more indebted Eurozone economies with problematic increases in financing costs.

"Unlike the Fed, the ECB is more worried that the increase in European government bond yields is getting ahead of the domestic economic recovery," says Elias Haddad, a senior FX strategist at Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

The need to keep financing costs favourable is a direct result of insufficient inflation and all its underlying causes, which are often said by policymakers to result from the overindebted state of some Eurozone economies, but which are also a result of the bloc's rules relating to national debt.

Europe's stability and growth pact, which is embedded in the treaties, has for nearly a decade attached an almost perpetual weight around the ankles of those economies by requiring year-after-year reductions in government spending.

The rules have been suspended through the pandemic and are widely expected to remain so until at least 2022, although an eventual necessary decision as to their fate could be the most important development for ECB monetary policy since the pact was agreed in the wake of the sovereign debt crisis.