Bulls and Bears Square Off Over the Euro

© Andrey Popov, Adobe Stock

Optimists are cheerleading the Euro higher on the back of revelatory growth, yet Euro-cynics point out that unemployment is still too high to start celebrating.

Big bank analysts are becoming increasingly polarised over their outlook for the Euro.

In the 'blue corner' we have the Euro-bulls (in the majority) who think that the Euro will rise strongly in 2018 on the back of a booming economy which is set to grow by almost 3.0%.

In the 'red corner' are the Euro-bears, who expect the currency to fall, mainly because unemployment in Europe remains too high.

Whilst it may not seem immediately clear how 'dole queue' and currency are linked, economic theory holds they are, albeit via a circuitous chain of economic causes and effects.

This starts with the idea that the more people there are in work the higher inflation tends to be because people earn and spend more.

When there are more people in work there are also less unemployed so employers have to bid higher to attract suitable candidates from an ever-dwindling pool.

The opposite goes for when there are fewer people in work: inflation itends to fall because spending and wages are lower.

When inflation rises central banks react by putting up interest rates to try to counteract the inflation be encouraging people to save rather than spend.

Yet higher interest rates also have a profound strengthening effect on the currency by attracting greater inflows of foreign capital drawn by the promise of higher returns.

For Euro -naysayers, the Eurozone's relatively high unemployment rate of 8.7% indicates low inflationary pressures and perennially low-interest rates.

The data seems to back this theory up as Eurozone core inflation is still at a relatively low 1.0% compared to the rest of the world.

The pro-Euro contingent, however, argues that regardless of the current situation the region is going through a game-changing growth spurt which will change things in the future.

Banks such as J P Morgan and Goldman Sachs expect the European Central Bank (ECB) to take earlier steps to reduce its QE stimulus measures which were only brought in to help during the crisis, and after QE is dismantled to start raising interest rates.

Euro-bears like Commerzbank, however, say that this will not happen because the ECB will not wind down stimulus as quickly as the market thinks because unemployment in Europe is at such a high starting point that even with vaulting growth it will not come down sufficiently to increase wage pressures to raise inflation, which will make the ECB reluctant to raise interest rates and consequently dampen the Euro.

Another argument put forward by Euro-enthusiast is that growth matters aa much as inflation.

They say there is a correlation between the growth rate differentials of two countries and the exchange rate.

The chart below provided by J P Morgan, for example, shows how the difference between Eurozone and US growth corrolates closely with EUR/USD.

Assuming this to be true, since the Eurozone is expected to grow faster than most countries in 2018 the Euro should outperform most currencies.

Unemployment and Currency Valuation

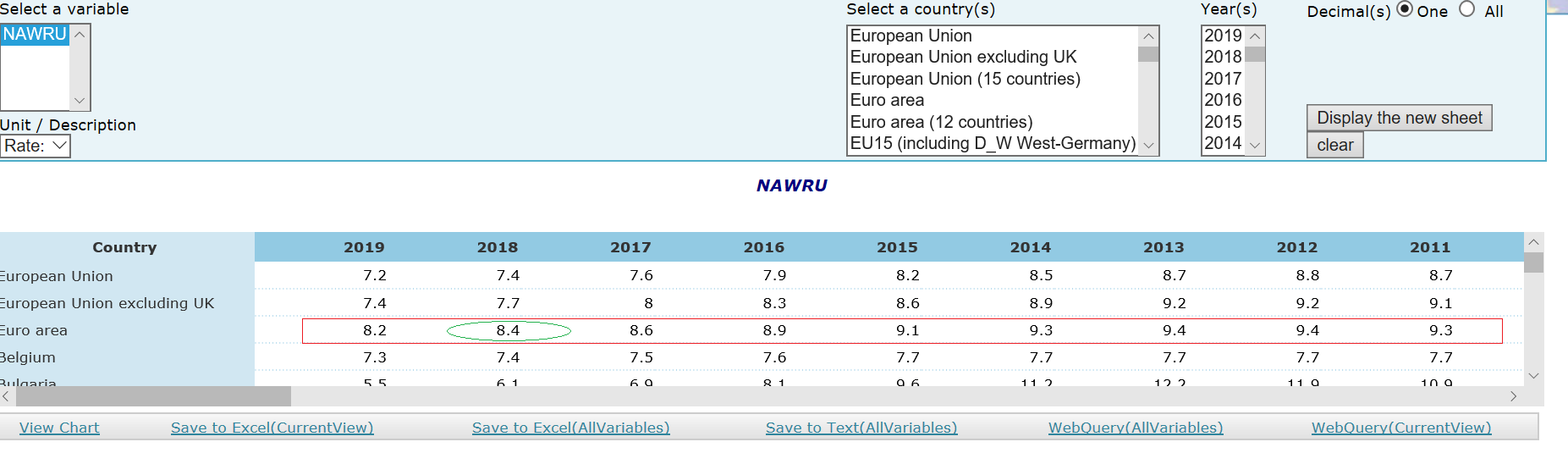

The level at which wages influence inflation is known in economics as NAIRU, or 'non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment', also sometimes called NAWRU.

Most large economic organistions, such as the IMF and OECD, produce estimates of NAIRU for different countries so one way to resolve the debate about the Euro would be to find a reliable estimate of NAIRU and compare it to the unemployment rate.

The best estimate of NAIRU we currently have for the Eurozone is 8.4%, from the European Commision, and this suggests that at 8.7%, the current rate of unemployment is quite close to the inflation 'biting point'.

Given unemployment has been falling at a pretty constant rate of about a basis point a month for several years now it should reach NAIRU in about 3-4 months time.

(Image courtesy of tradingeconomics.com)

Such a projection would suggest Euro bulls may be right and inflation, interest rates, and the exchange rate are likely to go up soon, yet such an interpretation may also be too simplistic.

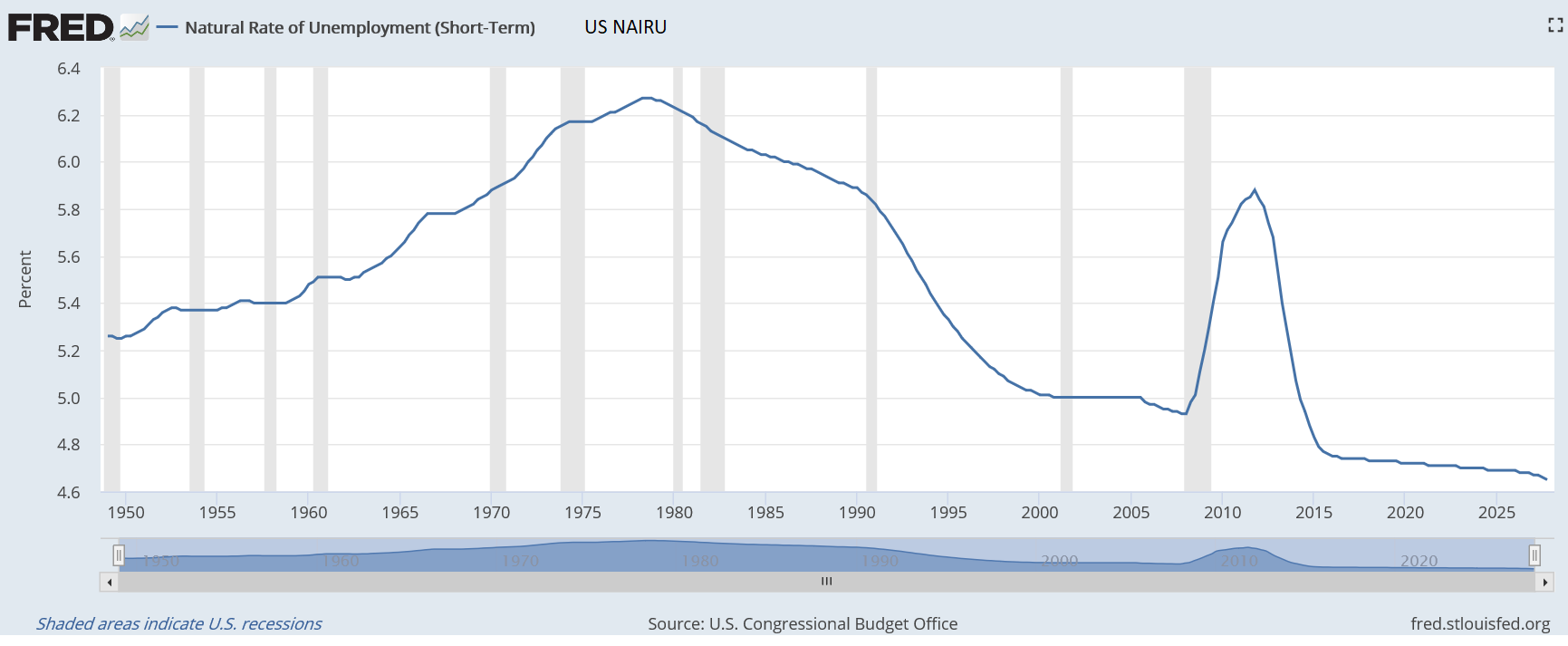

The main problem is that NAIRU is that it is not a fixed constant but rather it changes all the time.

Below, for example, is the chart of NAIRU in the US which shows how volatile it can be and how low it has fallen recently; the last estimate of NAIRU for the US was 4.73%, down from 5.07% in 2014.

The same goes for the Euro-area as the table of NAIRU results produced by the European Commision database shows below:

Therefore we have no way of ensuring that if the unemployment level falls to NAIRU it will still be at the same level - there is a good chance it may have fallen even lower itself.

This seems to have been the case in the United States where despite unemployment falling to 17-year lows wages have remained stubbornly low.

It is also the case in Australia and Japan which also have historically low levels of unemployment but still subdued inflation.

We have a similar problem in the UK where a very low rate of unemployment is still not having much of an upwards effect on wages.

Indeed, the low level of NAIRU in the UK was highlighted by Bank of England MPC member Michael Saunders in a recent speech where he said that NAIRU had now fallen to just below 4.5%.

Given UK unemployment is now at 4.3% that would suggest employment is leading to higher wage pressures, in the UK at least, but there is scant evidence of that so far, sugessting NAIRU may be even lower.

The Why's and Wherefore's

The problem of why low unemployment is not triggering higher wages has become a global concern and economists continue to question why this is so.

One factor put forward as a reason is falling worker productivity which mesures the wealth generated by work done.

Another rationale is globalisation which now means companies can source labour from abroad not jut their local area and this means competition from cheaper foreign workers keeps wages perrenially low.

“As unemployment declines further, wage growth will continue to pick up. However, the rise will be curbed by global competition in labour and product markets, technological improvements and lower negotiation power for employees in the wake of labour market reforms,” explains DNB Markets economist Kjersti Haugland in a recent note on the topic.

As far as the Eurozone is concerned, Haugland thinks it will be a full year before 'capacity utilisation' returns to normal, which is another way of describing when NAIRU will be met.

"There is still some slack left in the eurozone, but we expect the capacity utilisation in the currency union to return to normal by year’s end," says the DNB economist.

Get up to 5% more foreign exchange by using a specialist provider to get closer to the real market rate and avoid the gaping spreads charged by your bank when providing currency. Learn more here.