Bank of England Outlook: Interpreting the New Interest Rate Guidance

- Written by: James Skinner

"Given lags in the transmission of monetary policy to price developments, high inflation today does not, of itself, justify tighter policy today," BoE chief economist Huw Pill.

Image © Adobe Stock

The Bank of England (BoE) raised its interest rate again this week and gave new guidance that appears to leave everything rested on economic data emerging from the UK in the months ahead, energy prices and the response of companies and households to October’s uplift in the ‘energy price cap.’

There is an important context in which all of what the Bank of England says about the outlook for inflation and interest rates probably ought to be interpreted and this was set out in a May 20 speech by the BoE’s chief economist Huw Pill.

“Given the workings of the OfGEM price cap, the full impact of recent sharp increases in European wholesale gas prices will only be felt in most British household utility bills – and thus in UK consumer price inflation – in October. The inflationary impact of the war is therefore likely to be more drawn out in the UK,” he told the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) Cymru.

As it still stands, and at the time of the May forecast round, the BoE’s judgement was that recent and forthcoming increases in energy costs would reduce the ‘real income’ of businesses and households enough to leave the economy teetering on the edge of a recession by year-end.

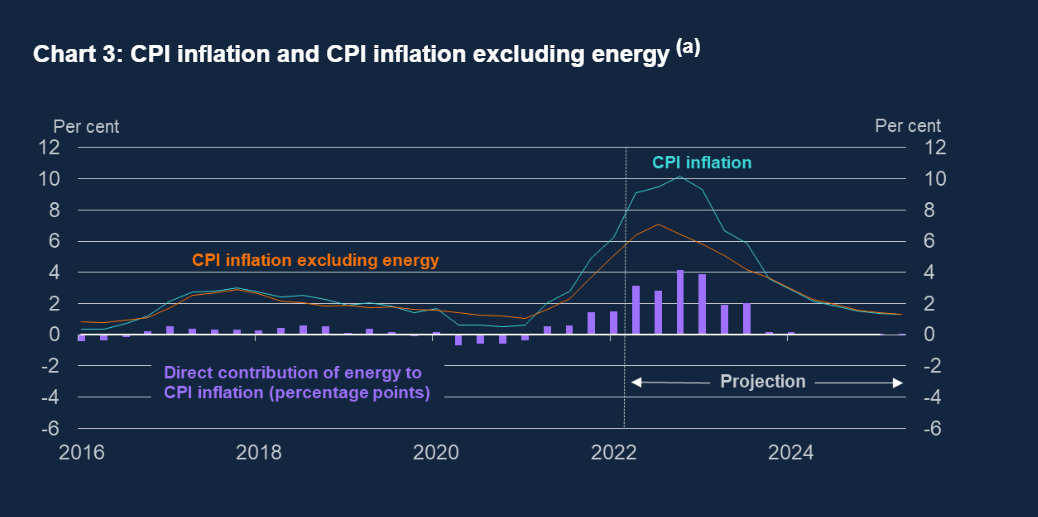

That growth impact was expected to weigh heavily enough on inflation to pull it down to just 1.3% in three years' time if, along the way, energy prices stabilised near to current levels and the BoE also continued to lift interest rates to the extent anticipated by financial markets.

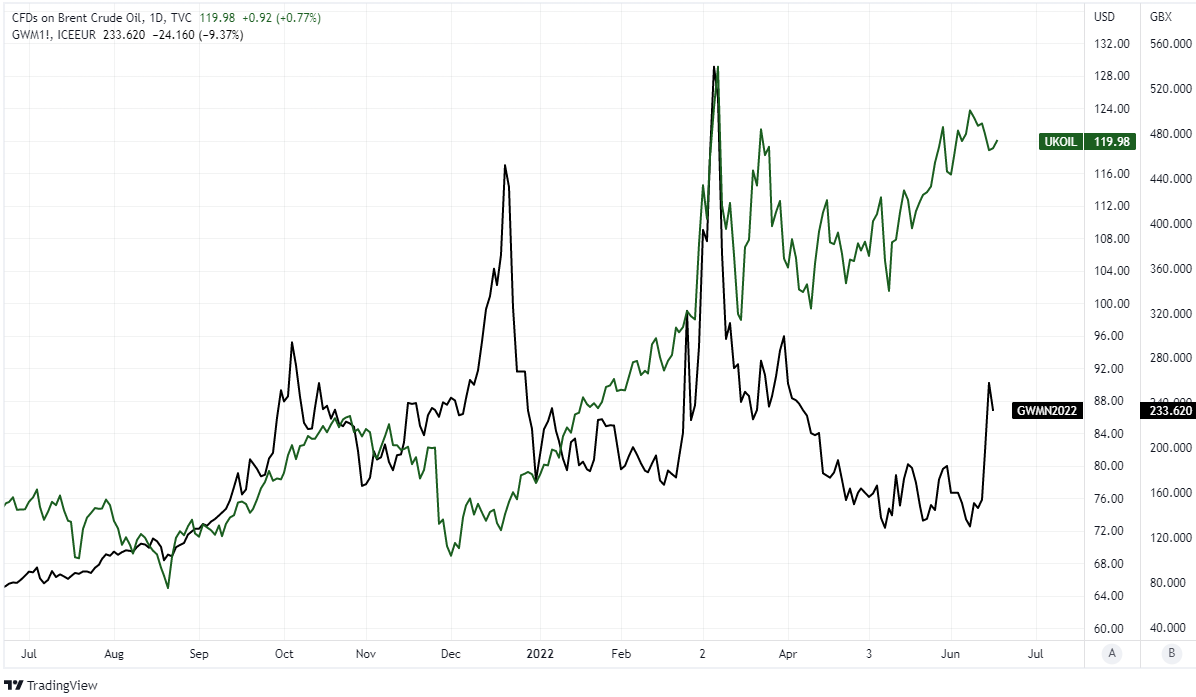

Above: Brent oil futures price and UK natural gas futures price.

May’s forecasts suggested the BoE is close to already having done enough with its interest rate to bring inflation back to the 2% target and that financial punters would potentially be left disappointed for having assumed that Bank Rate could rise by a further 1% between now and October.

But as was noted by chief economist Huw Pill, there are circumstances in which the outlook for inflation in two or three years time could change and either more or less be required of Bank Rate including the kinds of circumstances where energy prices rise further or fall from current levels.

"Given lags in the transmission of monetary policy to price developments, high inflation today does not, of itself, justify tighter policy today," Pill said in May.

"Policy has to be forward looking, calibrating the policy stance to be appropriate at a horizon of 18 months to two years, once the transmission lags unwind. And that is where the MPC’s May forecast gets more complicated," he added.

It may be relevant that the BoE has noted this Thursday that “Consumer services price inflation, which is more influenced by domestic costs than goods price inflation, has strengthened in recent months.”

Above: BoE's May Monetary Policy Report forecast for inflation.

Above: BoE's May Monetary Policy Report forecast for inflation.

But for further example, GDP growth and employment could rise or fall faster than expected during the months ahead or wages and other selling prices could rise faster than was anticipated after October’s increase in the ‘energy price cap’ and its subsequent impact has been felt.

All of this is important when it comes to interpreting the latest statement from the BoE and its new guidance on Bank Rate, which was almost non-committal.

“The scale, pace and timing of any further increases in Bank Rate will reflect the Committee’s assessment of the economic outlook and inflationary pressures,” the BoE said on Thursday.

“The Committee will be particularly alert to indications of more persistent inflationary pressures, and will if necessary act forcefully in response,” it added after lifting Bank Rate from 1% to 1.25%.

Financial markets responded to the announcement by revising their expectations higher and were on Friday pricing-in an even larger 50 bp increase for the August announcement, which would take Bank Rate to 1.75% and more than twice the peak level seen since the 2008 financial crisis.

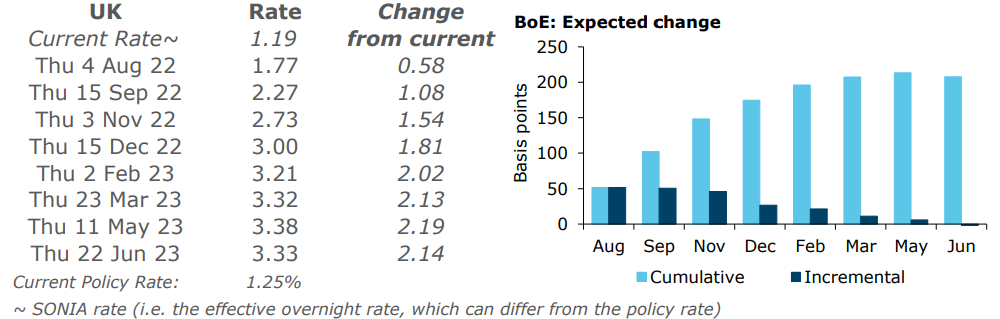

Above: Market-implied expectations for BoE Bank Rate at various intervals in the period ahead. Source: ANZ.

Meanwhile, market-implied expectations for Bank Rate at year-end rose from 2.76% to 3% on the nose and reflect a significant increase from the 2.4% level that was implied on the morning after the BoE’s May policy decision.

This is despite the few UK economic figures emerging since the May forecast release having underwhelmed both market expectations and the BoE's.

These include two GDP reports covering March and April as well as this week's employment data that had wage and salary growth running below the levels anticipated by both the market and BoE for the recent months.

“The economy had recently been subject to a succession of very large shocks. These shocks had pushed global energy and other tradable goods prices to elevated levels. Those price increases had raised UK inflation and, since the United Kingdom was a net importer of these items, would necessarily weigh on most UK households’ real incomes and many UK companies’ real profits. This real economic adjustment was something monetary policy was unable to prevent,” the BoE said on Thursday.

“These global shocks could interact with domestic factors, including the tight labour market and the pricing strategies of firms, and could lead to more persistent inflationary pressures. The role of monetary policy was to ensure that, as the adjustment in the real economy occurred, CPI inflation returned to the 2% target sustainably in the medium term, while minimising undesirable volatility in output. Monetary policy was also acting to ensure that longer-term inflation expectations were anchored at the 2% target,” it added.