Unemployment Has Doubled in UK Coronavirus 'Lockdown' to Highest Since February 2013

- Written by: James Skinner

© IRStone, Adobe Stock

- GBP/EUR spot at the time of writing: 1.1465

- Bank transfer rates (indicative): 1.1163-1.1243

- FX specialist rates (indicative): 1.1292-1.1361 >> More information

UK unemployment has more than doubled during the three weeks of 'lockdown' imposed on the economy in order to slow the spread of coronavirus, likely taking the April 2020 jobless rate up to its highest level since February 2013, Pound Sterling Live calculations show.

There have now been more than 1.4 million new claims for welfare benefits since the middle of March, Department for Work and Pensions Secretary Theresa Coffey told Sky News, which reflects around a 50% increase in the number of new claims reported at the beginning of April.

This more than doubles the 1.33mn number of unemployed reported by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for the three months to the end of January and is enough to lift the jobless rate to 7.9% and its highest since February 2013. The jobless rate was tracking 5.3% mid-March and 6.6% as of the end of March, earlier disclosures suggest, although March figures will not be released until May 19 given they're published with a 45-day lag of the period end. Tuesday, April 21 will mark the release of February data.

There were 32.98mn people in full and part-time work during the three months to the end of January 2020 and some 1.33mn who were unemployed but actively looking for work, the official definition of unemployment, which made for a jobless rate of 3.9%. However, there would be 2.73mn unemployed after the latest job losses are taken account of, which would lift the jobless rate to 7.9% if the size of the overall labour force remains the same.

"We expect a solid 100K three-month-on-three-month rise in employment and a stable unemployment rate at 3.9% in February...But all the focus will be on March vacancy and claimant count data, which will deteriorate sharply," says Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

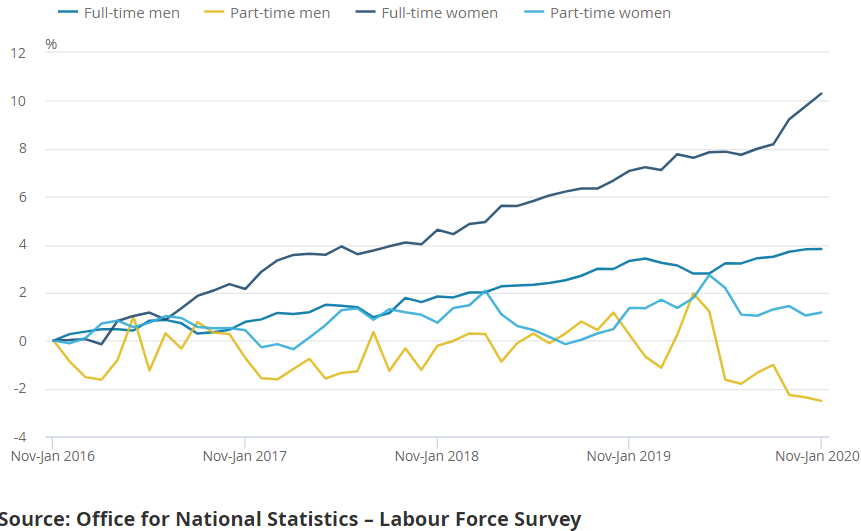

Above: Changes in full and part-time employment for men and women in the UK ahead of the coronavirus shutdowns.

The Office for Budget Responsibility said Tuesday that a total of 2 million jobs may be lost to the coronavirus in a downturn that could see GDP fall by 35% in the second quarter and lift the jobless rate to 10%.

As a result the watchdog has projected £273bn of government borrowing for 2020 that would lift the budget deficit to 14% of GDP while raising the debt-to-gdp ratio to 95% this year and above 100% next year.

The ONS will release February's jobs numbers on Tuesday, April 21 but these will reveal little about the impact that coronavirus containment efforts have had on the labour market and economy given the government response was mild until mid-March when it began advising citizens to steer clear of pubs, cafes and restaurants. It asked those businesses to close their doors less than a week later and was attempting to enforce a nationwide 'lockdown' by March 23.

March and April data will be where most damage is found but ONS methodology for defining unemployment could suppress the official measure until the 'lockdown' is lifted if for reasons related to the national shut-in, recent job losers tell the ONS they aren't 'actively looking for work'. If 'lockdown' leads the unemployed to abandon job searches then at least some of the jobless might not be recognised in the figures until economic activity begins to normalise.

"Our analysis points to an increase in the Euro area unemployment rate to 11 ½ % and a rise in the UK jobless rate to 8 ½ % by the middle of the year," says Sven Jari Stehn, an economist at Goldman Sachs. "The coronacrisis is likely to push the European economy into a deep recession this year...Looking across countries, we expect larger contractions in Italy and Spain than in northern Europe, including a 7.5% decline in UK real GDP in 2020."

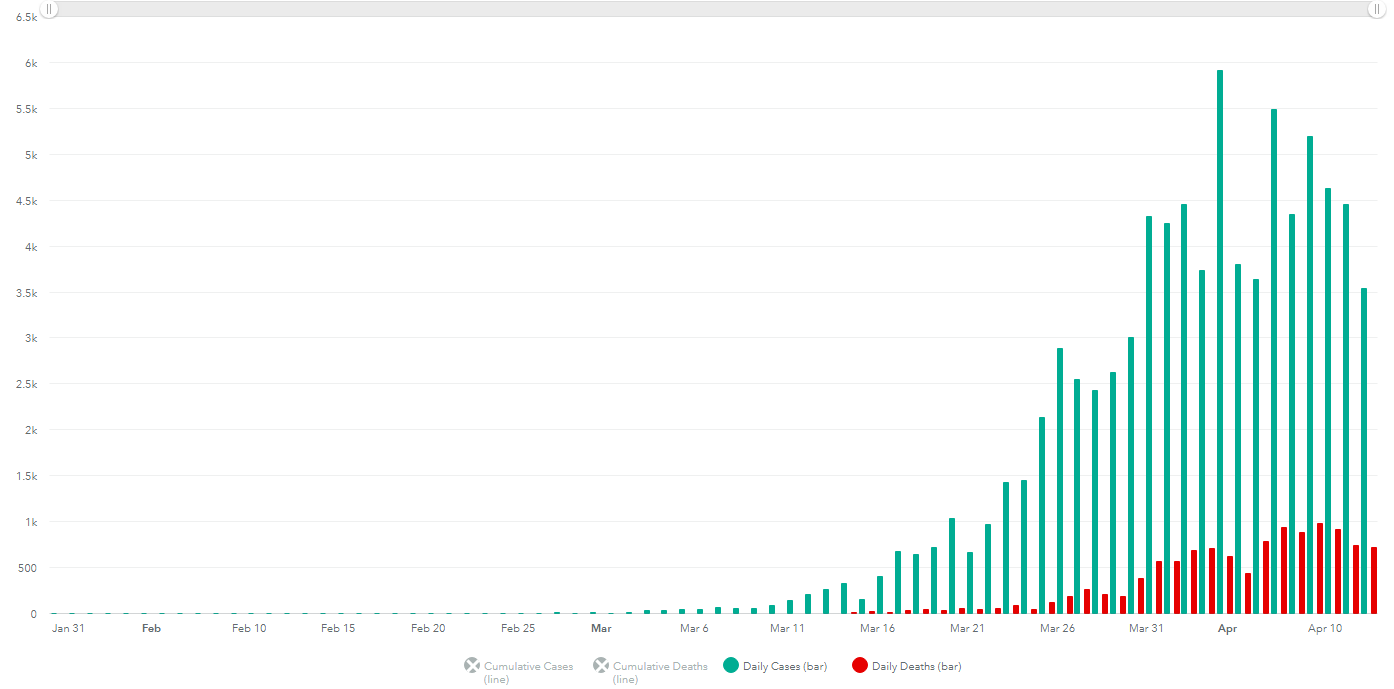

Above: New coronavirus infections and deaths, daily totals, in UK. Source: UK government.

The number of new coronavirus infections declared by government has been trending lower in the UK since April 05, indicating that the so-called peak in the outbreak could have passed although this doesn't mean the 'lockdown' of the economy will be lifted any time soon.

The 'peak' is the top of a statistical distribution around which the greatest number of new infections is clustered. But if the 'curve' of the distribution is of a 'normal' statistical bent then there could be a symmetrical six weeks before daily infection numbers fall back to the low double-digits of early March.

“We won’t know until the future whether or not the Bank of England has launched helicopter money as it depends if the rise in the money supply is temporary or permanent. But more important is whether it leads to much higher inflation. The markets don’t think it will and nor do we. If anything, it’s more likely that in a few years’ time policymakers will look back and decide their policies were too timid,” says Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics.

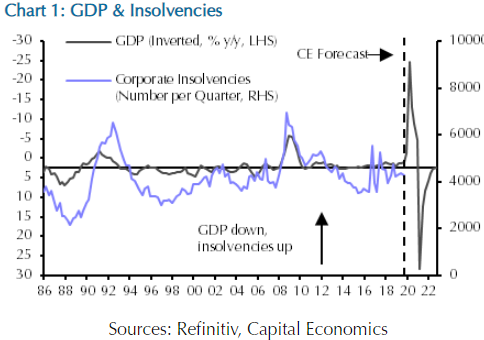

Above: Anticipated change in UK GDP growth and business insolvencies. Source: Capital Economics.

Lockdown has driven an abrupt stoppage of vast parts of the national economy, likely producing large double-digit falls in second-quarter GDP and a substantial hit for the first quarter, all of which has necessitated significant, unprecedented intervention from HM Treasury and the Bank of England (BoE).

Chancellor Rishi Sunak has offered to have the government pay 80% of workers' wages and made hundreds of billions of uber cheap and government guaranteed loans available to business in order to plug the 'lockdown'-shaped hole in the economy, while the BoE has all but said it will finance the fiscal splurge if it becomes necessary. But many still see big trouble ahead, with the government's measures better off viewed as a plug or bung for a hole in the economic ship than any form of stimulus.

"We’ve assumed a 25% contraction in GDP and that businesses struggle for about 15 quarters. That would be a much deeper fall in GDP, but a shorter period of disruption than in the GFC due to the short, sharp nature of this crisis, the unprecedented level of government support and because firms (apart from retailers) went into this crisis in a stronger position than they were at the start of the 1990s recession or the GFC. However, this would still result in about 110,000 businesses going bust over the next few years," says Thomas Pugh, an economist at Capital Economics.