Inflation Difficulty at BoE a Possible Sign of the Risks in Europe and Elsewhere

- Written by: James Skinner

"Due to the shift away from floating-rate mortgages towards fixed-interest products over the past decade, the pass-through of monetary policy to consumption via the housing market takes longer than in the past" - Berenberg.

Image © Adobe Images

The difficult inflation situation faced by the Bank of England (BoE) is in one way potentially a sign of things to come for the European Central Bank (BoJ) and any others presiding over monetary frameworks where the transmission of interest rate changes into the real economy is slower than it is in the UK.

The BoE raised Bank Rate from 4.5% to 5% this week in what may have marked a return to the larger-than-usual rate steps used briefly last year after official data from the UK suggested inflation had not fallen in May.

"The May figure was 0.3 percentage points higher than the expectation at the time of the May Report," the BoE said on Thursday.

"Bank staff analysis suggested that world export prices could account for a significant share of elevated core goods CPI inflation," it also later added.

UK inflation actually rose last month once the effect of food and energy price changes is set aside, suggesting forecast revisions may be likely in August while implying more uncertainty about how soon inflation could be expected to fall back to the 2% target.

But it's also a reason for thinking about inflation in Europe and other places where differences in the mortgage markets have potentially left some central banks with less potent or otherwise less effective monetary policy tools than the BoE's Bank Rate.

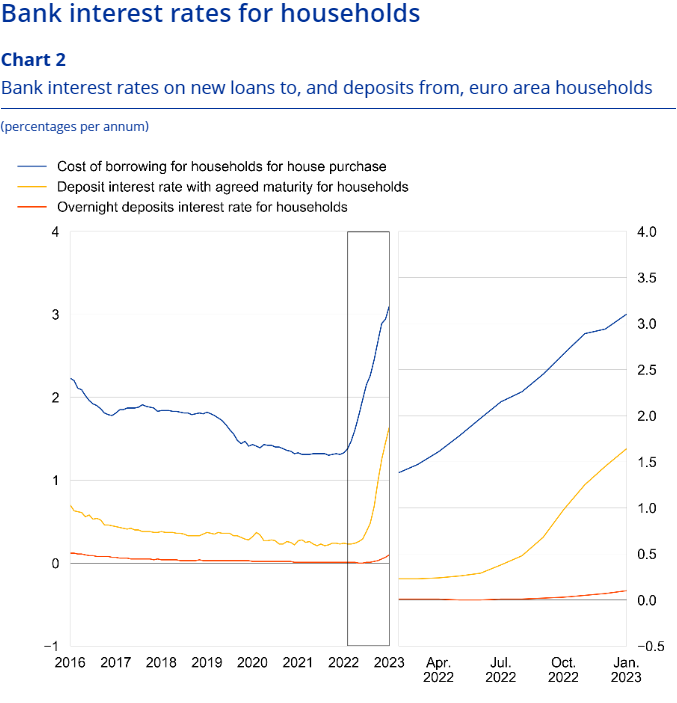

Source: European Central Bank.

Compare Currency Exchange Rates

Find out how much you could save on your international transfer

Estimated saving compared to high street banks:

£2,500.00

Free • No obligation • Takes 2 minutes

"The UK has a faster monetary policy transmission via housing than Germany and France (with their lovely 10 to 30yr fixed mortgages). And if services CPI is going to be hot for longer, I suspect the Euro Area’s will hold up better," says Jordan Rochester, a G10 FX strategist at Nomura.

Consumer choices, government regulations, central bank rules, and the availability as well as take-up of loans with longer fixed-term periods for the interest rate all make for sizeable differences in mortgage markets and the time over which changes in interest rates are passed through to households,

This "faster transmission" of BoE policy should mean changes in the Bank Rate then work more quickly to reduce inflation in the UK than changes in the equivalent interest rate in places where fixed-term periods for mortgage borrowing costs are longer.

Put differently, it should make Bank Rate more effective as a tool than rates at the ECB and elsewhere, potentially including the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and Federal Reserve (Fed).

“Due to the shift away from floating-rate mortgages towards fixed-interest products over the past decade, the pass-through of monetary policy to consumption via the housing market takes longer than in the past," writes Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg, in a note following the BoE decision.

“If the BoE overreacts to near-term inflation surprises, it may set the stage for an inflation undershoot once the full effects of its prior policy decisions play out. The BoE minutes suggest that the bank is aware of the risk – it may have chosen to act decisively now in the hope of not having to go much further in the future,” he said on Thursday.

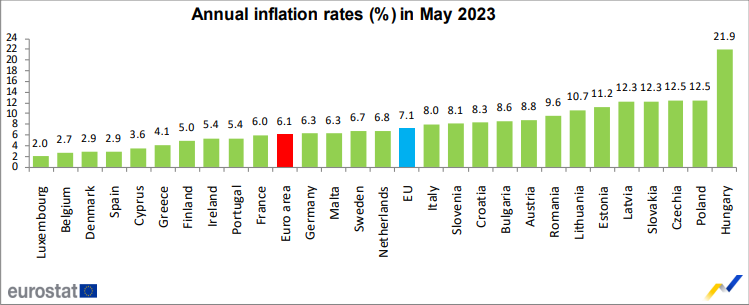

Source: Eurostat.

Compare EUR to USD Exchange Rates

Find out how much you could save on your euro to US dollar transfer

Potential saving vs high street banks:

$2,750.00

Free • No obligation • Takes 2 minutes

As far as the Bank Rate is more effective, it could also mean the ECB's battle with inflation will eventually prove to be harder and more prolonged than the BoE’s.

The mortgage market differences were covered here in more detail but it might also matter that UK mortgage rates are much more closely aligned with interest swap rates than they are with Bank Rate, and these are much closer to 6% than the current BoE rate of 5%

The risk of a slower transmission prolonging the return of inflation to the target in Europe is potentially amplified by the relatively healthier domestic economic backdrop in the Euro Area too, which slipped into a technical recession in the first quarter but would have grown at a robust pace if one-off factors were set aside.

Inflation is also lower in many of Europe’s large economies than in the UK but the levels are broadly similar while the risk of further increases is one the ECB is attuned to.

“Wage-sensitive components of core inflation remain strong and domestic inflation is rising. This configuration suggests that the external drivers of underlying inflation – namely rising energy costs and supply bottlenecks – are easing, but domestic factors – i.e. wage pressures – are becoming increasingly important,” President Christine Lagarde told a G30 summit last week.

“We are seeing our past rate increases being transmitted forcefully to financing conditions. Borrowing costs have increased steeply and growth in loans is slowing. In April, lending rates reached their highest level in more than a decade, standing at 4.4% for business loans and 3.4% for mortgages,” she added.