HM Treasury Penny Pinching Greater Threat to Economy than Deficit, Economists Say

- Written by: James Skinner

Image © Gov.uk

Britain's economy received its own shot in the arm this week when the ball began rolling on a global coronavirus vaccination programme, although the economy's recovery could be cut short if HM Treasury's concerns about the budget deficit lead to an unnecessary or premature return of austerity.

Pfizer and BioNTech's coronavirus vaccine is gradually being made available and more are expected to follow in the coming months, leading the government to relax its demands for social distancing and related curbs on activity that have come at a high price for businesses, people and the economy.

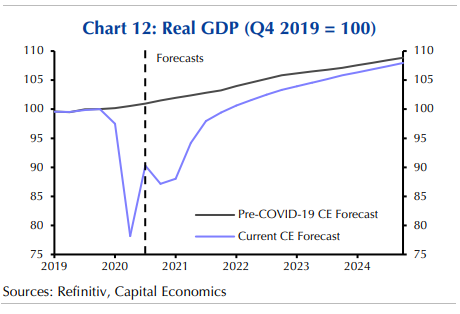

Vaccines, if effective, could reduce the threat of overloaded health services and enable normal life to resume, leading output from industries and spending among consumers and households to normalise.

That's unless HM Treasury and Chancellor Rishi Sunak are panicked, pushed or pulled into a calamitous course of policy action first.

"At some point, there may need to be a fiscal squeeze to pay for any lasting increase in spending caused by the COVID-19 crisis and increases in age-related spending. But the biggest danger is that fiscal policy is tightened too much too soon to fill a perceived hole in the public finances that never materialises," says Ruth Gregory, a senior economist at Capital Economics. "That could be self-defeating as it would lead to a slower economic recovery."

Source: Capital Economics.

Gregory and the Capital Economics team warned on Tuesday that "long-term scarring" would result from any premature decision by the Chancellor to withdraw pandemic-related support programmes or begin making other cuts to public spending, which would risk seeing companies and jobs endangered and may even necessitate greater cutbacks further down the line.

The warning is salient given the ominous words used by Chancellor Sunak in his opening remarks ahead of November's spending review. Sunak, who's effectively the government's chief accountant, told parliament that "Our health emergency is not yet over. And our economic emergency has only just begun."

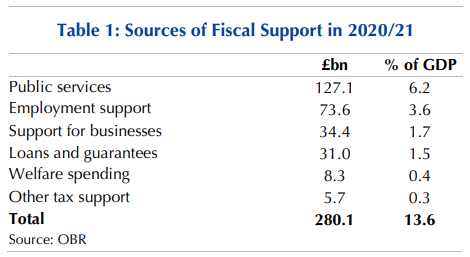

Sunak's November spending review came just days after the Office for National Statistics said the government had borrowed £22.3 billion and an amount equal to more than one percent of GDP in the prior month of October and that borrowing for the first seven months of the financial year was running at £214.9 bn, up 74% from the 2019 level.

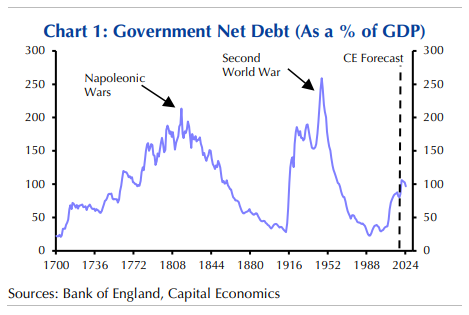

"The debate so far has been framed in terms of “how to pay” for the fiscal costs of the crisis. But it’s not at all clear which metric the government should be focusing on (the deficit, debt to GDP ratio, debt interest costs), nor what “paying for” the fiscal damage actually means," Gregory says. "When it comes to the budget position, this will only become a problem if the virus results in a permanent and significant increase in the deficit such that the debt to GDP ratio spirals ever higher."

Increased sums like those seen in October are among the factors informing November forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility suggesting that Britain could borrow a total of £394 billion or 19% of GDP this year as a result of government's acts in relation to the coronavirus and its initial neglect of the threat posed by the disease.

Source: Capital Economics.

These in turn have formed the basis for myriad suggested forms of corrective action including widespread tax increases, so-called wealth taxes and a return to the austerity that defined government by Britain's ruling Conservative Party under the leadership of David Cameron and his Chancellor George Osborne.

Actions often speak louder than words but in the case of Chancellor Rishi Sunak, November's words may matter more than actions. After all, the spending review was read off like a shopping list with no expense spared when it comes to coronavirus containment, and little sign of any reduction in support for households and businesses or services provided to the public.

But recent developments around defence spending show that November's commitments do not necessarily mean a financial retrenchment is not in the pipeline. Last month saw the government announce a supposed £16 bn increase in defence spending and to much fanfare, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson billing it as something that would "extend British influence" in the world and saying "The era of cutting our defence budget must end, and it ends now."

However, barely more than a fortnight on and the somewhat different reality is that "A further £2 million will be saved by not sending HMS Prince of Wales to America next year for essential training," according to The Telegraph, as the "military is to make £1 billion in cuts over the next year, with Navy Reservists suspended for the first time as part of sweeping savings." The article tells of a Ministry of Defence effort to fill "the £13 billion black hole Mr Wallace inherited when he took over the brief in July last year."

An aptitude among politicians for rhetorical sleight of hand might soon enable government ministers to claim to be supporting the economy, all the while pulling the rug through an attempted consolidation of its finances. On both counts the proof, or lack thereof, will be in the publication and eating of the economic data.

Source: Capital Economics.

Higher taxes and reduced spending could have significant implications for the economic outlook because irrespective of which way any so-called belt tightening is done, it still reflects direct net costs for the recovery of an economy that is, almost by definition, little more than the sum total of all spending in the country plus or minues a handful of adjustments.

"The pandemic will only cause a permanent reduction in tax receipts if it causes a permanent reduction in economic activity," Gregory says. "If the crisis means that the economy is permanently smaller in the long run, then most of the increase in the budget deficit is “structural” and there is less room for it to be eroded over time by the economic recovery. But if the size of the economy returns to the pre-virus trend, then most of the deficit is cyclical and it will narrow automatically as the economy grows."

Any return to the Cameron years of austerity would to at least some extent sabotage the recovery. However, the greatest threat to the rebound from this year's coronavirus-inspired collapse comes in the form of a premature withdrawal of the various support programmes put in place to aid companies and households through the disruption of 'lockdown' and social distancing measures that limit capacity and activity wherever imposed.

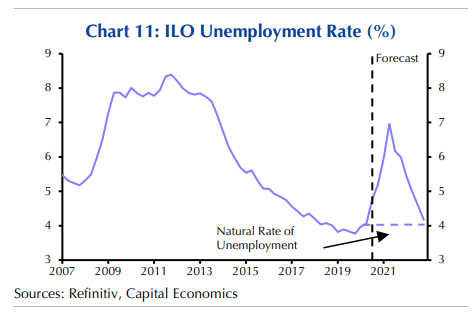

Gregory and the Capital Economics team say that any reductions in spending should be calibrated to match the recovery in private sector demand, with the speed of reduction determined by the time taken for either pre-pandemic levels of GDP to be restored or for unemployment to return to its 'natural rate' and earlier low. But they suspect that political considerations will lead the government into an earlier consolidation of the public finances that is less well thought out and more costly in the long run.

"The noises coming out of the Treasury seem to suggest that the UK government is keener than most other countries to enter into a period of belt-tightening. This might be driven by a political desire to prove that the Conservative Party is better at managing the public finances than the Labour Party. Or it may reflect a desire to lengthen the time between unpopular tax rises and the next general election," Gregory says in a Tuesday briefing to Capital Economics' clients. "It doesn’t make sense to announce a fiscal consolidation, when the fundamental state of the economy is still so poor and the tax base has not fully recovered. Instead, the tapering and withdrawing of policy support should be calibrated to match the recovery in private sector demand."

Source: Capital Economics.