This is More than Just a Trade War, its about Putting China "Back in the Box"

Image © White House

- Trade war may have longer to run as ‘trade’ is not the only factor

- Global strategic superiority and security issues also key

- Competing factions within U.S. administrations make signing a deal complicated

The historically high U.S. trade deficit may not be the only factor driving the U.S.-China trade war; other factors include politics, perceived national security risks and global strategic factors are at play.

Indeed, some of these proxy factors have unforeseen and far-reaching implications for the whole future of global trade.

Whilst from Donald Trump’s perspective, rebalancing the trade relationship with China may be the main motive for pursuing a trade war, there may be others in his administration who are in the fight for strategic purposes, says Robin Niblett, the Chairman of Chatham House (the Royal Institute for International Affairs).

“I think from Donald Trump’s standpoint it is a chance to reset the terms of trade the U.S. has worked on for the last 20-30 years, and get the advantage back to America,” says Niblett, “But I think for many people who are in his administration this is a long, multi-administration battle to put China ‘back in the box’ and to make it pay a price for stepping up and becoming a competitor of the U.S. on the global stage.”

Trump’s perspective is likely to be short-term and he probably wants a deal, partly so he can deliver on his election promise, and partly so he can go back to voters in the 2020 presidential elections and say “I set off, took a tough line and look what I got”.

The strategy hawks in his administration, however, may want to see deeper change and be willing to wait longer for it.

“So I think you have two different views: he wants to do a deal but I think many of his advisors are looking for structural change and it’s going to be a battle,” says Niblett.

In China, there are also competing priorities.

On the one hand, China needs a deal to prevent any further decline in economic growth so as to preserve the reputation of the Communist party, yet on the other hand, they don’t want to be seen to cave in too easily to Trump’s demands either. In both cases “the legitimacy and strength of the communist party is paramount,” says Niblett.

“Being seen to cave into the U.S. at this time - which is the way Donald Trump will talk about it, emphasising “winning” - is something which is incredibly difficult for this Communist party to do. We have lower rates of growth. Unemployment rising a little bit. A little bit of unpredictability about the rates of growth going forward. In the end, they need to balance out how it looks to the Chinese public.”

One conspiracy theory around talks is that the Chinese may be waiting for a change of leader in the White House and would prefer to negotiate with a Democrat president rather than Trump and so may be willing to wait to do a deal until after the 2020 elections.

The U.S’s blacklisting of Huawei highlights another factor in trade talks, which is that of national security risk. The U.S. doesn’t want exposure to Huawei technology for fear its own technological intellectual property secrets could be leaked and/or stolen by the Chinese, and out of concerns, Huawei’s tech could be used as a ‘trojan horse’ by Chinese intelligence service to gain access to U.S. secrets.

Despite Ren Zhengfei, the founder and CEO of Huawei refuting accusations of providing a ‘backdoor’ to intelligence services and intellectual property theft, the fact is it is impossible to be 100% certain the Chinese authorities might not use the company as a conduit into the heart of the west.

Huawei has been thoroughly vetted by British authorities before setting up its 5G network and although they say they haven’t found any ‘backdoors’ through which the Chinese intelligence services might gain access, it’s almost impossible to be watertight in this regard.

“You can never be sure with the China 2017 national intelligence law, that some Chinese individual, if not the company could be ordered to do something at some point. As we know the Chinese have been able to spy very well on European industrial secrets as well as other things without the need for Huawei,” says Niblett.

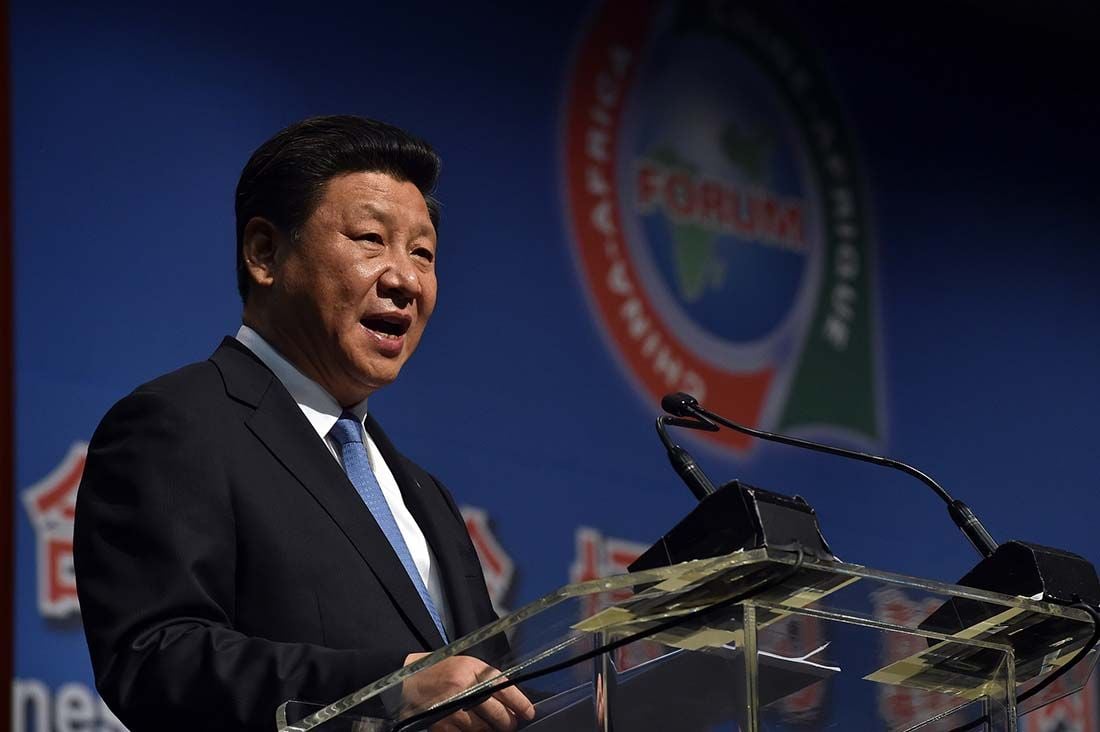

Above: Xi Jinping, Chinese President. File image © GovernmentZA, image Reproduced Under CC Licensing

The national security implications of global trade are very real, says Karl Eikenberry, the U.S. Asian security initiative director at Stanford University and former deputy chair of the Nato security committee.

“The interconnection between trade and high technology is very real and it is new for the U.S. We have always had trade issues with China for the last 3 decades. What’s new is that now when we look at trade between the two countries we find that an increasing amount of commercial commodities and technologies have national security implications, they have military implications,” says Eikenberry.

Whereas in the 1970s, at the height of the cold war, about 70% of military technology was produced by proprietary companies specialising in the defence sector, now you would have to flip that on its head and say about 70% of defence technologies come out of what is being developed by the commercial sector, mainly in Silicon Valley.

“So for the first time we have the phenomenon where trade negotiators are sitting side-by-side with those that are trying to preserve the crown jewels of international security and high technology, and I think it profoundly complicates economic exchange. There is an expression ‘the securitisation of the economic exchange’ and that is what we have seen happen over the last few years,” says Eikenberry.

This may explain why European car imports were deemed a ‘national security risk’ by the U.S. trade department back in April. Onboard computers in cars are so sophisticated now that they might have components with national security implications, the imported car becoming a modern-day Trojan horse.

“The cutting edge tech is coming out of the commercial sector,” says Eikenberry, who adds that, “the national security concerns the U.S. and its allies have about Huawei are very real.”

From a financial market perspective, if the trade war worsened, Chatham House’s Niblett is not so sure the Chinese government has the ‘unlimited firepower’ to prop up the Chinese economy through a protracted trade war, and although Yuan depreciation helped curtail the impact of U.S. tariffs when they were art 10% the rise to 25% means the Yuan would have to depreciate substantially to offset the tariff rise, something the authorities are unlikely to allow, given their fears about capital outflows, triggering a death spiral in the currency, as happened to the Turkish Lira.

In relation to the outlook for Huawei, the future looks bleak.

“Chairman Ren has always had a desire to get into the U.S. market but he thought it would be difficult, which is why he is focusing on Europe and the UK in particular. He’s imagined he could do a global strategy without the U.S. That if the U.S. ever tried to freeze them out, which they have done in lots of sectors and areas prior to the current spat, there would be another global strategy,” says Niblett.

The irony is that despite the apparent wisdom of focusing on the rest of the world at the exclusion of the U.S. Huawei cannot escape the U.S’s tentacles.

“What they are discovering is that they cannot even have a global strategy, if the U.S. is opposed, because the U.S. has brought the hammer down on allowing firms that have any aspect of U.S. technology, certainly over 20%, to interact with Huawei,” says Niblett.

The big driving force is U.S. strategic long-term gain as the U.S. does not want China to be a rising tech competitor.

“It is sending a signal to the Chinese government we will not let you play, not only in our space but we are going to impose a cost on you being a technology leader globally. This is more about the strategic gain less about the backdoors in Huawei,” says Niblett.